A look at FaceApp, TikTok and the rise of ‘data nationalism’

Gordon Ramsay may have just given an obscure Russian company the right to do whatever they want with his face.

A look at FaceApp, TikTok and the rise of ‘data nationalism’

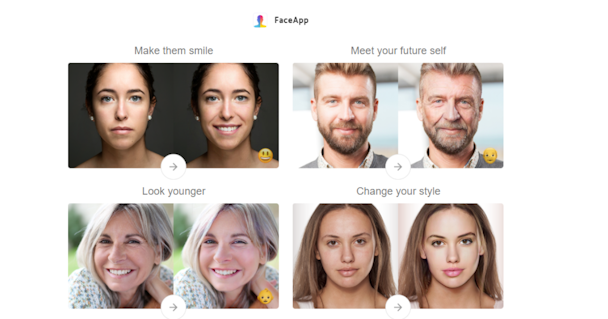

Last week, the mobile application FaceApp released a new feature that allows people to upload headshots of people and turn the subject’s face decades older. The function went viral on social media networks with people cracking jokes about their potential future selves.

But there appears to be a darker side. FaceApp – and some other foreign-made, popular apps such as TikTok – are facing serious safety and security concerns that are also signs of the single, global internet fracturing into a collection of country-specific internets.

FaceApp’s controversial past

FaceApp was released in 2017 and originally allowed users to edit faces in photographs in ways such as adding a smile, subtracting a few years or applying a ‘hotness’ filter.

Later that year, the app added options to apply makeup, put on a ‘hipster’ beard, change genders and – most controversially – see how people would look if they were another race. The app currently has more than 100 million installations in the Google Play store alone.

During last week’s #faceappchallenge, politicians, everyday people and celebrities such as Ramsay posted pictures of older versions of themselves and others.

Always read the fine print

But there were just two problems: FaceApp’s terms of use and privacy policy.

The former includes this language:

What does that mean in plain English? When anyone uploads a photo to FaceApp, they grant the company a permanent license to do whatever they wish with the image and any information associated with or contained within the image. In other words, FaceApp may indeed be able to use Ramsay’s face and name – and those of an estimated 150 million other people – however it wishes.

Now, look at the privacy policy:

FaceApp collects metadata – as well as other personal information – and can store the data in any country in which the company or its partners operate.

First, it appears to me that FaceApp is attempting to get around GDPR by potentially storing the personal data of EU users in non-EU countries. But that is non-compliant. Whether peoples’ information is protected under GDPR depends not on where their data is stored but where they are physically located.

Second, data of people from outside Russia is likely stored in Russia. When you visit the country for business, the first thing you notice is that LinkedIn is blocked. Russian law mandates that internet companies store the information of Russian people on servers in the country, ostensibly for their protection. Microsoft – LinkedIn’s owner – refuses to do so.

I believe – but have no evidence – that Microsoft is worried that the Russian government would obtain users’ personal information from LinkedIn if the servers were there. In democracies such as the US and UK, legal authorities usually need court orders to get such material. But Russia is more authoritarian. (Just see what websites are blocked there.)

Hypothetically, the Russian government can now obtain anything that anyone uploaded to FaceApp. The country’s reported interference in the Brexit referendum and 2016 US presidential elections is indeed historical cause for concern. Two days ago, hackers reportedly found out that Russia’s national intelligence service has had a program since 2009 named Nautilus that collects information on social media users.

Now, is it any wonder that the Democratic Party in the US is warning 2020 presidential candidates not to use FaceApp and a senator there is calling on the FBI to investigate the mobile application?

I contacted FaceApp founder and chief executive Yaroslav Goncharov for comment. He sent me, in part, the following statement:

“All FaceApp features are available without logging in, and you can log in only from the settings screen. As a result, 99% of users don't log in. Therefore, we don't have access to any data that could identify a person.

“We don't sell or share any user data with any third parties. Even though the core R&D team is located in Russia, the user data is not transferred to Russia.”

I then asked Goncharov specifically where the company’s cloud data centers are located, whether data in foreign countries is mirrored or otherwise transmitted to Russia, why FaceApp processes images on outside servers rather than on user smartphones, why the company needs such extensive user licenses, and what FaceApp will do with the images.

He did not respond further.

Look at TikTok too

Now, FaceApp is not the only popular but controversial product from an authoritarian country.

David Carroll is the American media professor who helped to break the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandal. He and British journalist Carole Cadwalladr are featured in a Netflix original film on the topic, The Big Hack, that will premiere this week on 24 July.

Two months ago, Carroll investigated TikTok and found that user data may have been transferred to China from the time of the app’s creation until the company changed its practices and privacy policy in February 2019.

Also note that TikTok only did so after agreeing to a $5.7m settlement with the US Federal Trade Commission for illegally collecting the personal information of children there when TikTok was named Musical.ly. The app is currently under a similar investigation in the UK.

China is even more authoritarian than Russia. The Chinese government can certainly obtain whatever it wants from tech companies there. And note that the US banned companies in 2012 from using networking equipment made by Huawei, a Chinese telecom supplier and phone manufacturer, over fears of spying.

“Consumers have the burden of knowing the provenance of software and making choices about where their data gets processed,” Carroll said in an interview. “Obviously, undemocratic regimes like Russia and China will result in data practices that some people should object to if they care about such things.

“As for the risks of sharing facial data with autocratic regimes like China, if folks are not worried about helping to train Chinese algorithms, then they probably haven’t read anything about the surveillance-driven ethnic cleansing against the Uighur population in Xinjiang.”

I contacted TikTok and asked if the company sent data from people outside China to the country before February 2019, if foreign user data is or had been stored or processed in servers controlled by the Chinese government, under what conditions the Chinese government could access data from people outside of China, and if the company or Chinese government keeps copies of material that people delete.

A TikTok spokesperson said: "Protecting user privacy is a critical priority for TikTok. As part of our overall commitment to transparency, we are working with an independent, US-based internet privacy firm to audit our practices and confirm that we are employing industry-leading standards for the storage and protection of TikTok user data."

Is FaceApp doing AI training?

Whenever people ‘prove’ to websites that they are human by identifying stoplights, roads and cars in images, they are actually helping to train Google’s driverless car technology.

FaceApp, then, could be a similar way to advance facial recognition platforms. After all, Facebook’s ten-year challenge earlier this year was accused of doing just that. No for-profit business does something just to do something -- there is always a self-serving reason.

“Any app gathering data points that could lead to facial recognition should be of concern especially when it’s being used by government agencies, foreign companies or foreign intelligence,” security awareness expert Robert Siciliano told MarketWatch.

Thankfully for those who have privacy concerns, some facial recognition systems are surprisingly bad. The technology that London’s metropolitan police use is 96% inaccurate. A student in New York is suing Apple for $1bn after the company’s platform allegedly caused him to be falsely arrested for theft.

But those issues detract from the darker side of the industry. According to a Forbes report in 2018, a former Israeli intelligence officer has created a massive facial recognition database using faces acquired from what Facebook and YouTube users post online. Facebook itself is pushing people to use the technology. AI researchers are allegedly scraping photos of faces online by the millions.

“Because of the uniquely identifying nature of our faces and our inability to change them, cataloging and storing peoples' faces in a database that can be mined indefinitely is problematic,” a Privacy International report last week stated.

“A biometric map of someone's face isn't just used for unlocking smartphones, it is now a highly-prized commodity by governments and tech companies used to train algorithms and for facial recognition-enabled mass surveillance. In the future, such biometric maps could be used for all sorts of purposes that people may not anticipate.”

It also makes me wonder whether advertisers will soon mimic the worlds of Blade Runner and Minority Report and use facial-recognition software to further the rise of surveillance capitalism with interactive advertising. That might be enough to make me throw my smartphone in the Mediterranean Sea.

‘The new, narcissistic age’

FaceApp and TikTok – and probably most other social media platforms – are taking advantage of a negative trait in human psychology. (Other mobile apps, such as Tinder, can also collect 800 pages of personal information on users.)

“People are excessively wanting to put themselves out there for personal recognition, fame and individuality – it’s the new, narcissistic age we live in,” William Soulier, chief executive and co-founder of the influencer marketing platform Talent Village, said.

“What these people don’t realize is that they are signing away all of their image rights and data when they use these apps. This means any piece of content that is put into the FaceApp domain means that the app owns all the rights to use it anywhere as they please. They could even post a user’s face on a billboard in Leicester Square, if they wanted to.”

“Both apps are frighteningly popular,” Kingsley Hayes, managing director of data breach and cybersecurity law firm Hayes Connor Solicitors, said. “They are both fun and easy to use, and few, if any, will bother to read the terms and conditions.”

“While consumers are increasingly aware of both the value and vulnerability of their personal information, fun apps like these may be seen as harmless fun but can potentially lead to significant risks in the long run.”

Goncharov, FaceApp’s chief executive, did not respond to my specific questions on whether user images will be used for facial recognition training.

The ‘age of the splinternet’

Whether Russia and China now have untold amounts of personal information on westerners might not even be the most significant issue. Thirty years after Sir Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web, we are now seeing individual countries customizing their own internal internets.

LinkedIn does not work in Russia. China has erected The Great Firewall. Kazakhstan is now intercepting all HTTPS traffic. Companies with users in the EU must follow a higher privacy standard. Numerous countries may regulate social media networks in their own individual ways. India temporarily banned TikTok.

“It’s surreal that fun apps are a potential threat model in the age of the splinternet, but that’s where we are,” Carroll said. “As an American, I trust American tech more than Chinese or Russian tech because the law is on my side with regards to government surveillance.”

“Anyone paying close attention is probably becoming a data nationalist, whether they like it or not.”

The Promotion Fix is an exclusive biweekly column for The Drum contributed by global keynote marketing speaker Samuel Scott, a former newspaper editor and director of marketing in the high-tech industry. Follow him on Twitter. Scott is based out of Tel Aviv, Israel.