How journalism can survive and thrive

Should mainstream news outlets first and foremost create profits for shareholders or neutrally, objectively and thoroughly educate the public? That is the battle for the soul of journalism today.

From bias to neutrality and back

The idea that journalists should be neutral and fair is relatively recent. In the US, newspapers took sides during the Revolutionary War. Throughout the 1800s, publications were essentially propaganda tools of political parties. Late in the century, ‘yellow journalism’ yelled sensationalist headlines, published scandal-mongering stories and even helped to provoke the mistaken Spanish-American War.

But business changed things in the early 1900s. Publication owners discovered that offering advertising was far more profitable than selling subscriptions. Of course, having more readers meant that the newspapers could charge more money — so the goal was to attract the widest audience possible through being moderate and non-partisan.

The US Civil War decades earlier even played a role. The cost of sending telegrams with battlefield reports was expensive, so correspondents developed the inverted pyramid along with a concise and ‘just the facts’ writing style that would later become the basis of ‘objective journalism.’

Still, objectivity did not become the only standard. For the first two decades of the 20th century, ‘muckraking’ investigative journalists focused on exposing corruption and other misdeeds in the government and corporate worlds. In the 1990s, talk radio became dominated by right-wing hosts. For years, the highest rated cable TV news network has been the rabidly conservative Fox News.

The growth and decline of advertising

Objectivity became the goal in most journalism because it was the most profitable model in the mid-20th century world of reaching a mass audience and attracting the most advertisers.

But then the advertisers started to disappear. Classified advertising was the biggest source of revenue for newspapers until Craigslist and then websites such as eBay, Realtor.com and Cars.com appeared and let people sell stuff to each other for free or cheap. According to the Newspaper Association of America, classified ad income fell 77% from a peak of $19.6bn in 2000 to $4.6bn in 2012.

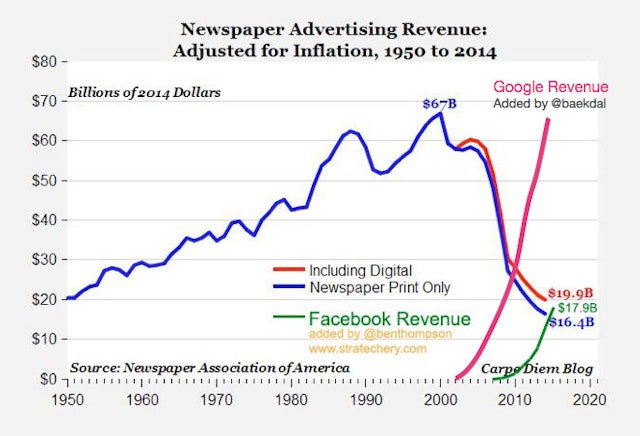

And that was only the beginning. Analyst Thomas Baekdal added Google’s revenue to this chart that has become infamous in media circles:

Facebook has become the trendy company to criticise – and I have done my fair share – but it was Google that drew first blood. And it was a massacre.

Today, everyone is selling ad space. Amazon became the number three digital ad platform in the US last year. Apple is reportedly looking to distribute ads on websites such as Snapchat and Pinterest. Microsoft has LinkedIn. Even Uber wants to become an ad company. Just remember what early Facebook employee Jeff Hammerbacher told Bloomberg Businessweek in 2011: “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads.”

But the problem is that there are only so many advertiser dollars to go around. And what does basic economics say happens when the supply of ad space increases? Prices – and therefore publisher revenue – decrease.

The decline in advertising revenue is especially hurting an industry that was never a gold mine in the first place. (“No one goes into journalism to get rich,” a boss once told me.) Even online publishers – which have much lower operating costs – are in trouble as Google and Facebook suck up more advertiser spend and everyone else competes for the scraps.

Take Mashable. BuzzFeed News. Vice Media. Mic. Gigaom. All of these publications and more have shut down, sold for a fraction of a prior valuation or are greatly missing revenue projections. And I’m not even discussing net profits. In January 2019, more than 2,000 media jobs were lost over a period of two weeks at media companies including BuzzFeed, Vice and the Huffington Post. Most of those publications were funded by venture capital – and I still have no idea why.

“You cannot apply tech startup economics to a journalism company and expect it to operate ethically,” Aram Zucker-Scharff, ad tech engineering director at The Washington Post's Research, Experimentation and Development group, rightly tweeted. “All VC-based startups are operating on a set of incentives which are already unethical, but doubly so for journalists.”

Perhaps those venture capitalists should have talked to my former boss. VCs ruin everything – good journalism does not and should not scale. (The only success story I have heard: Sarah Lacy recently announced that she has sold Pando, a news site she founded that covers Silicon Valley. But the reasons for the sale are not entirely positive.)

Maybe news should not be profitable

“Someone once said that the worst thing that ever happened to journalism was that 60 Minutes became profitable,” Dan Kennedy, a media analyst and journalism professor at Northeastern University in Boston, told me.

Broadcast TV news programming in the US was never meant to be profitable. The big three networks – ABC, CBS and NBC – delivered the news to the country for the prestige for their brands and to satisfy Federal Communications Commission public service requirements. And they gladly did it at a loss.

Then, CBS released 60 Minutes in the late 1960s. The news magazine was almost like a television show in which the journalists were the protagonists who were the modern muckrakers exposing the bad guys. It was a Nielsen top 10 hit. The owners of news organisations of all types have wanted similar results ever since.

“Over the past two generations, we've seen newspapers that were once family-owned, supported by modest profits, fall into the hands of corporate chains,” Kennedy added. “Before the economic model for newspapers began to be undermined by the internet, some of these chains insisted on profit margins of 30%, 40% or even 50%. Now, as the business declines, these chains continue to insist on short-term gains, cutting their newsrooms to the bone while squeezing out the last few drops of profit.”

Contrary to what the VCs who funded the failed media outlets probably think, real journalism is not hiring glorified bloggers, placing them in a mind-numbing open plan office and underpaying them to pump out countless pieces of clickbait content widgets with accompanying ads. Real journalism takes time and money to travel, research, question and review. Real journalism takes talent.

How journalism can survive

But today, it needs help. Here are some possible solutions to explore.

Build an original brand. Successful media companies today do not function like the aforementioned widget factories. Stand for something. Personally, I like what The Washington Post has done in these troubling times.

Unless you are a general interest publication such as BBC or a weekly newspaper that is the only outlet covering a small town, it will become increasingly important to focus on a specific niche. TechCrunch is the main outlet covering the high-tech world, but Lacy’s Pando, for example, is a subscription-based outlet that focuses partly on the seedy underbelly of that industry.

To this day, most private British publications are associated with a certain political viewpoint. In many instances, journalism in the US today is echoing that practice and somewhat returning to the days of yore. Yes, we should always start with the facts and not fall into ‘yellow journalism’ again. But the facts can be discussed in different contexts and from different angles.

Scott Galloway recently wrote the brand era is “drawing to a close”. I would argue that it has never been more important. In a media context, your brand is what you write and which writers you publish. (And in advertising, marketing’s dynamic duo of Les Binet and Peter Field have found that at least 50% of tactical media spend should be on brand rather than activation.)

More features, less news. There are countless websites, online news aggregators and discussion forums where people can learn what happened yesterday. Unless you cover a niche such as The Drum and the marketing and media industries, most publications do not need to spend too much time reporting on so-called ‘straight news’. Publish fewer articles – but better ones. It is always about quality over quantity.

The differentiation between outlets should lie in features, analysis and opinion – the types of original articles with original thoughts that appear nowhere else. But, of course, the pieces should be measured and reasonable – not the outrage that made people believe that a European country blew up an American ship.

Diversify your offerings. As news itself becomes less profitable, media companies are looking elsewhere. The Times of Israel recently introduced a ‘membership’ option that provides “special status and benefits”. The Boston Globe has live events. The Drum has awards competitions. TechCrunch has the Disrupt conference series. The New York Times has a branded content studio.

Such offerings lead to additional revenue streams from memberships, ticket sales, sponsorships, productions for clients and award entries. Further, all of the departments can support each other. Events and awards competitions build the brands of news outlets as authorities. Ads alongside editorial can gain customers for those additional services. (But please keep editorial and everything else separate.)

Promote the top of the funnel. Google and Facebook have sucked away ad revenue from publishers by convincing companies that only the bottom of the funnel matters. After all, most online ads are actually direct response and not advertising.

Say I search Google for “buy Gap clothes” and click on an advertisement in Google AdWords. That click only resulted from the fact that I heard about Gap clothes somewhere else first and was convinced that I wanted them. Searches do not occur in a vacuum. Online channels are great for direct response at the bottom of the funnel, but traditional media is generally best for building brands at the top of the funnel.

Media outlets should promote that reality – especially in light of studies that I have previously highlighted. But it will take a lot of work to convince digital-addicted marketers of that fact today.

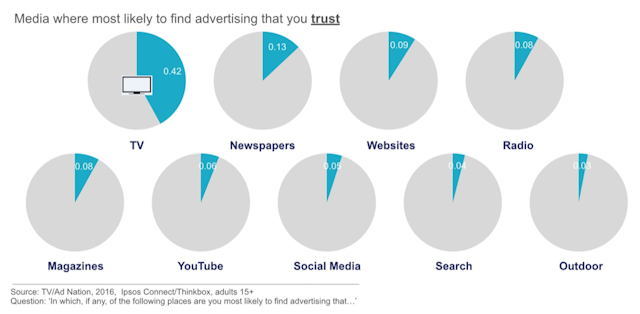

Highlight the trust factor. According to the Poynter Media Trust Survey, 76% of Americans trust their local TV news stations and 73% have confidence in their local newspapers. That number falls to 47% for online-only news outlets. In contrast, people do not trust search and social media ads.

Raise hell about ad fraud. I have never understood why the traditional media world does not band together to launch a massive PR campaign about how much of the online advertising world is fake. If I were consulting for them, it would be my first recommendation. One of the biggest myths in marketing today is that ad tech cut out the middlemen – but in reality, it just replaced one set of expensive middlemen with another.

Further, The Correspondent published last week a groundbreaking report on how online advertising might be “the new dot com bubble”.

Basically, the researchers found that advertisers do not distinguish between ‘selection effects’ and ‘advertising effects’. (Selection effects are when people see an ad and click, buy, register or download but were already going to do so anyway regardless of the advertisement. Advertising effects are when the ad directly convinces them to do something they were not already going to do.)

Explore non-profit options. News does not have to make huge profits. Kennedy, the professor and media analyst, suggested years ago that major media outlets should be run by universities or other non-profit organizations. His recommendation seems to be unfolding as the Salt Lake Tribune in the US recently became the first news organisation to receive non-profit status.

My thought: quality news, like electricity or water, could be considered a public good. So, maybe its availability should not be left to private, for-profit corporations. Electric and water companies are public utilities. The public good should not be up for sale.

After all, where has for-profit journalism led? In the US, CNN provides 24/7 coverage whenever an airplane crashes or an attractive white woman goes missing. Fox News has become little more than a mouthpiece for Donald Trump’s White House. Both do little to inform the public.

What about Facebook News?

Facebook recently released Facebook News, a section of the social media platform that will feature articles from a set of publishers selected by the company. Time will tell if it will help those media outlets, but the principle is what is most worrisome.

According to Pew, 43% of adults in the US now get their news through Facebook. Having one company -- that is controlled by one person -- making the news consumption decisions for millions should terrify everyone.

One inclusion is deeply worrisome. Facebook refuses to release a full list of every news outlet in the section, but credible reports have surfaced that far-right Breitbart News is among them.

“When you hear that Breitbart – well known for publishing bigoted content, their infamous ‘Black Crime’ tag for articles and demonstrable disinformation – is among the ‘trusted’ news sources hand-picked by Facebook, it loses immediate credibility,” Matt Rivitz, the founder of the activist organisation Sleeping Giants, told me.

Sleeping Giants publicly shames advertisers into stopping ad campaigns on websites such as Breitbart News. Ads there have plummeted 90%.

“Breitbart's speciality is weaponised propaganda, not journalism,” Kennedy added.

To survive and thrive in the future, media outlets should probably avoid a devil’s bargain and be more creative instead. Thinking beyond maximising profits might just be a good start.

The Promotion Fix is an exclusive biweekly column for The Drum contributed by global keynote marketing speaker Samuel Scott, a former journalist, newspaper editor and director of marketing in the high-tech industry. Follow him on Twitter. Scott is based out of Tel Aviv, Israel